About a month ago, on April 24, I took a tour of the Hanford facility outside of Richland, Washington, and it was awesome.

Hanford is the most contaminated nuclear site in the country. It’s also the nation’s largest and most expensive environmental cleanup project. So why would anyone want to go there?

I myself went because the subject is fascinating to me, and because the hazardous waste is, if not quite contained yet, at least identified, and the tour guides keep you well away from it. Other people on the tour seem to have had various reasons for going. I detected anti-government/anti-tax skepticism, patriotic historical curiosity, and a couple of people who were there because they live in Richland and had never been.

Unfortunately, and for reasons that were never made clear, the DOE doesn’t allow photography on the tour. We had to leave our cell phones in the car, so I don’t have any pictures of the actual tour. This was lame on the one hand, but also not lame, as otherwise I would have been taking pictures all day and not actually seeing everything. It left me time to just look and take it all in. I’ll try to figure out words to describe it.

First of all, it was a nice warm sunny day. The tour bus leaves from a nondescript building on the southern edge of the Hanford site, a few miles Northwest of downtown Richland, after everyone has been signed in and made to watch the first of several DOE propaganda films about the history of the site and the cleanup effort.

To summarize: Hanford was a plutonium factory. That’s all it was for. From 1944 to 1989, the US government at Hanford made plutonium for America’s nuclear weapons arsenal, starting with the bombs detonated at Alamogordo and Nagasaki. The bombs themselves were made elsewhere. The plutonium was made here.

And it was made. You think of plutonium as an element, a substance to be procured from nature. Plutonium doesn’t exist in the Earth naturally, however, at least not in any practical amount anywhere it can be mined, so has to be manufactured. You do that by transmuting uranium. It’s like alchemy.

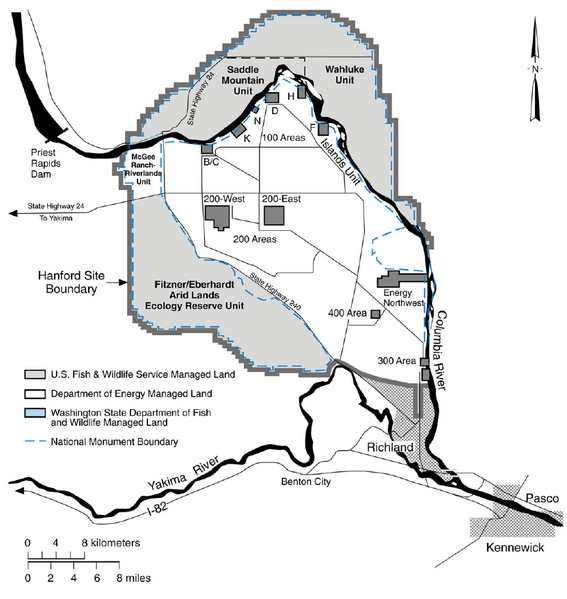

It’s also insanely messy. They started by processing uranium into a form that could be placed in aluminum fuel rods. That occurred at the 300 area, in the southeast corner of the site. Those rods then went to the 100 area — the reactors — placed at intervals along the Columbia river.

These were the first full-scale nuclear reactors, though they didn’t produce electricity. What the bomb makers were after was the tiny amount of plutonium that’s produced in a sustained uranium fission reaction. That this reaction also produces an enormous amount of heat was in fact a nuisance. 30,000 gallons of river water per minute were used to cool just one reactor’s fuel rods. This water contacted the rods directly, not through a series of heat exchangers as is the case in more modern reactors. As a result the water coming out was radioactive, and was left to stand in pools for some time (enough for the more volatile isotopes in the water to decay a bit) before draining back into the Columbia.

The irradiated fuel rods then went (carefully) to the 200 area, where the uranium and plutonium were separated in some godawful chemical voodoo that left behind insane amounts of contaminated waste for proportionately minuscule amounts of plutonium.

This went on for nearly half a century, in secret.

The manufacturing process and the waste are only part of the story though. Another, equally fascinating piece is how the site came together in the ’40s.

The site was picked because it had a lot going for it — lots of land, lots of water for cooling reactors, lots of electricity from the Grand Coulee dam, it was remote, and sparsely populated. The (mainly) farmers living in the towns of Hanford and White Bluffs were booted out, and thousands of workers brought in, who built the place in just 18 months. They had no idea what they were building.

The tour spans over 5 hours and takes you along the route of the plutonium manufacturing process (300 to 100 to 200), stopping at various sites for presentations from DOE employees and contractors about the site’s history and the cleanup effort. A large part of the tour centers on B-reactor, which was the first of the aforementioned 100-area reactors to be operational and is now a national monument. The last stop is just outside the vitrification facility, which is an enormous construction process in itself, though unlike the original Manhattan project is taking forever to be built. It won’t go online for another decade at least.

I’d say though that the best part of the tour is the insane contrast between the natural beauty of what is, for the most part, a very large tract of undeveloped land, and the poisoned industrialized bits scattered around the place. The history of the site, its purpose, the insanity of the Manhattan project, itself contextually located within the insanity of World War II, weighs heavily on the whole scene if you let it. Which I did, ’cause that’s how I roll.

You can sign up for tours at the Hanford/DOE website, and I recommend it. There are a limited number per year, only during the Spring and Summer. When registration opens it fills up pretty quick, but people seem to drop out periodically so it helps to check back often.

Of the things I was allowed to photograph, here are some.

Firstly, the requisite road trip pictures. I take millions of these. The second shot is one I like to take most times I approach Vantage, of the place my VW Beetle broke down in ’98 on my way to the Gorge for Page/Plant. I’ll never forget.

After the tour I went back into Richland and took a photo of the weirdly-shaped hotel I stayed at (from the air it would look like a question mark) and hung out at Howard Amon Park.

Heading back to Seattle I stopped at a couple of spots, including the Wanapum Dam, and Wanapum State Park.